Buying Stocks on Margin Has Exploded - One More Sign of a Coming Crash?

Americans are buying more and more securities on margin — essentially borrowing money to buy stocks — and analysts are sounding the alarm.

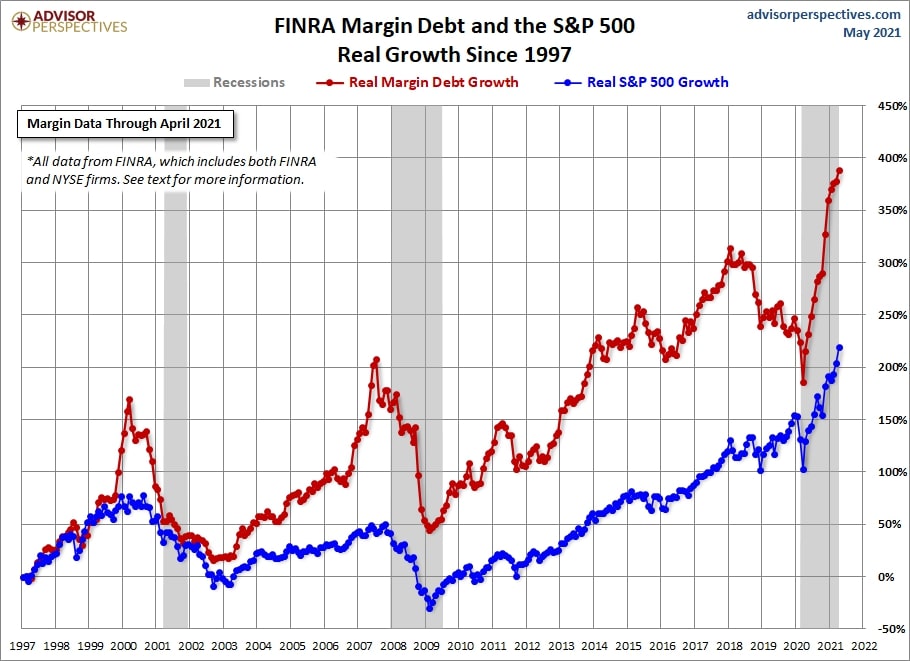

FINRA’s latest report showed that debit balances hit an all-time high in April at $847 billion, a 61 percent increase from April 2020’s $525 billion. Notably, when margin debits hit new highs, there is often a correction in the stock market, or even a crash, shortly thereafter.

Essentially, as debt amounts hit net highs, the market often hits fresh lows shortly thereafter.

The connection between the two indicators is striking, and analysts are worried.

What Would It Take to Get You Into a Stock Today?

Margin is a feature added to a non-retirement taxable account that allows clients to borrow money to buy securities. Typically, they are allowed to borrow up to half of their existing account value.

In a bull market, securities bought on margin will accumulate faster than if the client solely used the cash available in the account — leveraging the overall investment. If the securities rise higher than the amount charged in interest, the investor can turbocharge the overall investment.

The problem comes in when the value of the securities falls below the margin threshold, typically 50 percent of the overall value of the account. This can result in a margin call, where the investor must deposit additional cash, or the brokerage firm may sell off securities to bring the account below the margin requirement.

Margin Calls and the 1929 Stock Market Crash

Back in the 1920s, as ordinary people became enamored with the stock market, they could borrow a lot to buy stocks. They often needed a cash deposit of as little as 10 percent of the value of their portfolio.

[firefly_poll]

When the Federal Reserve raised the interest rate from 5 to 6 percent in August 1929, customers quickly found themselves pushed into margin calls. In his book “The Great Crash,” economist and historian John Galbraith called out margin buying as a primary cause of the crash.

“People were swarming to buy stocks on margin — in other words, to have the increase in price without the costs of ownership. This cost was being assumed, in the first instance, by the New York banks, but they, in turn, were rapidly becoming the agents for lenders the country over and even the world around,” Galbraith wrote.

“One of the paradoxes of speculation in securities is that the loans that underwrite it are among the safest of all investments. They are protected by stocks which, under all ordinary circumstances, are instantly saleable, and by a cash margin as well.”

Stockbrokers today would laugh at the notion of loans underwriting stock purchases as “among the safest of all investments.”

The tragedy for millions of investors was that when the market crash came, their investments plummeted in value, and they were on the hook for their huge margin balances.

The Market Today

Today’s stock market bears little resemblance to that of 90 years ago, particularly in terms of restrictions and regulations.

Rising margin debts reveal that investors are optimistic about the overall market, and investor optimism is often a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Nevertheless, with the inflation rate at its highest in 13 years, a housing bubble seemingly surpassing that of 2006 and an unemployment rate of 6.1 percent, all eyes are on the market as the most immediate, real-time indicator of the health of the economy.

And President Joe Biden is now looking to nearly double the capital gains tax rate from 20 to 39.6 percent, which might cause investors to cash in now to avoid a larger tax bill later.

It is never a bad idea to take some money off the table when you are ahead.

This article appeared originally on The Western Journal.